Presence - 1976 / LED ZEPPELIN

La historia de LED ZEPPELIN, probablemente (al menos para quien suscribe) el grupo más importante de la historia de la música, ha sido documentada hasta el hartazgo, así como sus discos han sido revisados, criticados (en este caso mayormente para bien, y de manera bastante abrumadora) y poco menos que estudiados hasta niveles obsesivos (como suele ocurrir con los grupos de este calibre), por lo que no tiene mucho sentido, casi cuarenta y tres años después de su desaparición como grupo, volver a hablar de lo mismo, ya que es probable que ya se haya dicho todo sobre ellos.

Así que no me voy a detener haciendo la habitual introducción previa acerca del grupo en cuestión, ya que además de lo inservible de la misma, unas cuantas cosas ya fueron dichas en la entrada sobre los guitarristas, al hablar de JIMMY PAGE. Dejo el enlace de la entrada para quien esté interesado.

Pero a pesar de todo, sí que voy a comentar uno de los discos de la banda, partiendo de un cierto paralelismo entre lo que fueron las carreras de Led Zeppelin y BLACK SABBATH en los años setenta. Y es que ambos grupos, además de similitudes musicales y el papel fundamental de ambos en la creación y desarrollo del rock duro y el heavy metal, la procedencia (todos los músicos de ambos grupos, quitando Page y JOHN PAUL JONES, son de la zona de Birmingham), la amistad entre ellos, la fama, el éxito y los excesos, compartieron una cosa curiosa en lo que a su discografía en esa década se refiere.

La era de Sabbath en los setenta, con OZZY al frente, abarca ocho álbumes de estudio, y como ya comenté en la entrada sobre DIARY OF A MADMAN, los seis primeros son muy famosos y de mucho éxito (vuelvo a recordar aquí la famosa frase de HENRY ROLLINS acerca de sólo poder confiar en ti mismo y en los seis primeros discos de Sabbath), pero los dos últimos están envueltos por una bruma de crisis en el seno del grupo y malas decisiones de todo tipo, resultando ser dos discos que podrían considerarse distintos, experimentales y sobre todo fallidos.

En ese sentido, a casi todo el mundo interesado en cierta medida en el grupo, le son familiares BLACK SABBATH y PARANOID, ambos de 1970, MASTER OF REALITY (1971), VOL. 4 (1972), SABBATH BLOODY SABBATH (1973) y SABOTAGE (1975), y la inmensa mayoría de las canciones que se contienen en ellos no necesitan presentación. Pero la cosa cambia con TECHNICAL ECSTASY (1976) y NEVER SAY DIE! (1978), los discos más raros, menos exitosos y menos llamativos de esa época del grupo.

|

| Black Sabbath, colegas brummies |

Y lo curioso es que con Led Zeppelin pasa algo muy parecido, ya que, si dejamos de lado el hecho de que los dos primeros discos del grupo salieron en 1969, su discografía en los setenta está compuesta también por otros ocho álbumes de estudio. Y de nuevo, a los dos primeros de 1969 (LED ZEPPELIN I y LED ZEPPELIN II), les siguen LED ZEPPELIN III (1970), LED ZEPPELIN IV (1971), HOUSES OF THE HOLY (1973) y PHYSICAL GRAFFITI (1975), todos muy conocidos, exitosos y llenos de canciones famosas. Y que hacen seis en total. Pero qué hay de PRESENCE (1976) e IN THROUGH THE OUT DOOR (1979)?

Aquí la cosa cambia. Estos discos no son ni tan nombrados ni tan conocidos, y tampoco (teniendo siempre en cuenta que estamos hablando de Led Zeppelin) tan exitosos. En el caso del segundo, un disco experimental, difícil de clasificar y que no pillo por mucho que intente acercarme a él con otra mentalidad y pensando que no se trata de un disco habitual de Led Zeppelin, se cumple en gran medida lo comentado con esos dos discos de Sabbath (aunque como ellos, éste también tiene alguna canción que me encanta, tres en concreto).

Pero no del todo con Presence, que es el disco que voy a comentar y que es un disco especial por varias razones. Y además, como ya he dicho antes, qué sentido tiene volver sobre WHOLE LOTTA LOVE o KASHMIR por enésima vez? Muchos, muchísimos, han hablado y escrito sobre esas canciones y otras muy famosas del grupo mucho antes e, indudablemente, mucho mejor que yo. También sobre Presence, por supuesto, pero me guardo en la manga el as del encanto que pueda tener hablar, ya no sólo de un disco de este grupo, sino de uno menos habitual y con cierto aire maldito. Y en lo que a mí respecta (y aquí es donde se distancia este disco de lo comentado acerca de su sucesor o de esos dos discos de Sabbath), Presence es un disco genial. No perdería el tiempo por aquí hablando de cosas que no me gustan, con todas las que hay que sí, y con todo el tiempo que lleva idear y escribir cada entrada. Es más, me voy a lanzar a hacer una afirmación bastante audaz con respecto a Presence (un disco no muy estimado por la crítica y los estudiosos de la banda, algunos de los cuales lo acusaron en su día de precipitación, falta de inspiración y necesidad, e incluso aburrimiento), y es que para mí es, junto a LZ II y LZ IV, el disco más completo del grupo.

El disco sólo tiene siete canciones pero tronco, esto va a ser difícil. Nada es simple o asequible con este grupo, empezando por el respeto que su propio nombre inspira.

|

| Jimmy Page, master and commander |

A mitad de los setenta Led Zeppelin eran la banda más grande del mundo, habiendo dejado atrás a cualquier otra en lo que a venta de discos y entradas se refiere. Sus historias acerca de excesos y depravación (exageradas o completamente reales) se unían a su estatus musical y no parecía haber nada que pudiese parar al grupo (pero ya se sabe que las caídas desde tan alto duelen más). De hecho, en 1974, incluso habían creado su propio sello discográfico, SWAN SONG (el nombre viene de una canción que no llegó a incluirse en Physical Graffiti y que diez años después se convertiría en MIDNIGHT MOONLIGHT, una canción que apareció en el disco THE FIRM, del grupo de igual nombre y corta vida que Page formó con PAUL RODGERS en los ochenta), cuyo logo (EVENING: FALL OF DAY, de WILLIAM RIMMER, 1869) con una figura humana con alas es más que famoso y aparece en todo tipo de memorabilia del grupo. Dicho sello sirvió para editar los discos del grupo y además incluyó a otros artistas, aunque duró poco tras disolverse Led Zeppelin.

Presence salió a la venta el treinta y uno de Marzo de 1976, pero es un disco que no fue planeado. Ellos no tenían en mente un disco de estudio. La explicación es que el grupo había estado girando tras la edición de su disco anterior, Physical Graffiti (el primero editado por Swan Song, con un éxito descomunal a todos lo niveles), a principios de 1975, y se tomó un descanso con la idea en mente de continuar con dicha actividad en directo más tarde ese mismo año, pero en Agosto, ROBERT PLANT y su señora sufrieron un accidente de coche bastante serio mientras estaban de vacaciones en Rodas. Ella estuvo cerca de perder la vida y Plant, por su parte, tuvo lesiones que impidieron cualquier actividad en directo, por lo que la gira se canceló y Led Zeppelin se vieron obligados a un cambio en cuanto a sus actividades a corto y medio plazo.

|

| Robert Plant, golden god |

Esto llevó a que, durante su recuperación (fuera de Inglaterra, por lo visto, debido a la condición de exiliados fiscales de los miembros del grupo), el cantante empezase a escribir una serie de letras, trabajo al que se uniría Page y del que resultaría la idea de hacer un nuevo disco (Presence, por supuesto), empezando los ensayos en Octubre, en Hollywood, cuando se unieron Jones y JOHN BONHAM. Esto también supuso que todas las canciones, menos una, fueran creación del dúo formado por cantante y guitarrista, siendo la restante una creación del grupo al completo.

El disco fue producido por Page (que trabajó junto al ingeniero habitual KEITH HARWOOD) y se grabó en los estudios MUSICLAND, de Munich, en un tiempo récord, ya que los ROLLING STONES tenían reservado poco después el estudio para grabar su disco BLACK AND BLUE. Plant grabó sus partes en una silla de ruedas, debido a sus lesiones, y en general lo que leo acerca de esas sesiones de grabación tan apresuradas es completamente insano, mayormente en lo que tocó a Page (que debido a la situación asumió el mando casi de manera exclusiva) y Harwood, ya que estamos hablando de hasta veinte horas diarias de trabajo durante cerca de veinte días.

Se comenta que como el disco se terminó justo el día anterior a la fiesta americana de Acción De Gracias, Plant sugirió que se llamase Thanksgiving, idea que se desechó en favor del nombre final, que hacía referencia al aura o presencia especial que los miembros de Led Zeppelin sentían que había cuando trabajaban juntos.

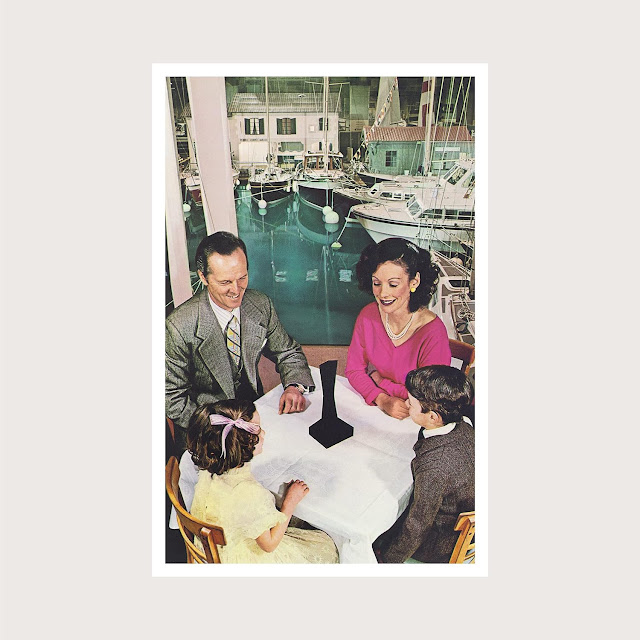

En cuanto a la portada, decir que es horrible. Ésta, y todo lo relativo al diseño, volvió a estar a cargo del grupo artístico conocido como HIPGNOSIS (junto al diseñador gráfico GEORGE HARDIE), que preparó una serie de fotos centradas en torno a un objeto negro llamado, de manera muy original, THE OBJECT, y que pretendía reflejar la fuerza y, de nuevo, la presencia del grupo, que era tan poderosa que no hacía falta que estuviese presente (en palabras de STORM THORGERSON, cofundador de Hipgnosis). La portada muestra una familia a la mesa, rodeando dicho objeto, y por detrás se ve una especie de puerto deportivo con unos barcos que, por lo visto, se había creado de manera artificial para un evento a mitad de los setenta en el EARL'S COURT ARENA de Londres, donde LZ habían llegado a vender todo el papel cinco noches seguidas a principios de 1975.

|

| Presence |

Decir que, de todas formas, en la reedición del disco de 2015, la portada cambia de color y su fondo negro y las demás variaciones la hacen bastante más interesante. Como curiosidades decir que, primero, las fotos interiores querían dar al disco la apariencia de un número de NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC, y que la niña de la contraportada era una tal SAMANTHA GATES, que había aparecido junto a su hermano (STEFAN) en la famosa y controvertida portada de Houses Of The Holy, en la cual unos niños en pelotas ascendían el GIANT'S CAUSEWAY, en Irlanda Del Norte.

|

| Presence, en su reciente reedición |

Y en líneas generales poco más que decir acerca del disco, antes de entrar de lleno en su contenido, aparte de que se grabó por los muy conocidos cuatro miembros de siempre del grupo (el grupo dejó de existir en cuanto uno de ellos faltó) y del hecho de que a pesar de su éxito (llegó a lo más alto en USA y Reino Unido), la crítica estuvo bastante dividida y a día de hoy es, históricamente, el disco menos vendido de Led Zeppelin.

Ah, sí! Muy importante. Este disco es el único del grupo en el que no se utiliza ningún tipo de teclado ni instrumentación adicional. Sólo guitarra, bajo y batería, además de armónica en una sola canción y (dicen, ya que me he de fijar mejor porque no lo pillo) algo de guitarra acústica en otra, ya que el grupo se centró más en el rock duro y menos en la relativa diversidad de discos anteriores. En todos los discos de Led Zeppelin (menos en In Through The Out Door) hay monolíticas canciones de rock duro, junto a algún tema acústico, algo más experimental o algún guiño a otros estilos, mientras que Presence se concentró sólo en lo primero, como si todo el álbum estuviese lleno de canciones del estilo de ROCK AND ROLL, DAZED AND CONFUSED, THE OCEAN, CUSTARD PIE o OUT ON THE TILES, dejando de lado temas tipo GOING TO CALIFORNIA por un lado, o IN THE LIGHT por otro, pero manteniendo a la vez serios niveles de complejidad en algunas de las composiciones. Y es que Page domina el disco de manera casi total, algo que se antoja lógico al tener en cuenta lo ya dicho acerca de que el guitarrista y Plant empezaron a trabajar en el disco sin Bonham y Jones, durante el tiempo que pasaron juntos en plena recuperación del cantante, y al no estar éste en plenas condiciones Page asumió más responsabilidades y se nota.

Todo lo comentado, junto a la situación del grupo en aquella época, que supuso que LZ no pudiesen girar para presentar un disco por primera vez (las lesiones de Plant hicieron que LZ no pisasen un escenario en todo 1976) y la escasa presencia de sus canciones en el repertorio en directo del grupo (voy a dejar de lado el hecho de que algunas de ellas sí han sido interpretadas por Plant y Page en sus aventuras post-Zeppelin, sean esas las que el grupo sí llegó a tocar u otras), dan a Presence cierto aire maldito, como ya comenté. Y para colmo, el disco quedó un tanto eclipsado por el estreno ese mismo año de la película THE SONG REMAINS THE SAME (que mayormente recogía grabaciones del grupo en directo en el Madison Square Garden neoyorquino, en 1973) más la edición del disco homónimo en vivo, uno de los discos en directo más famosos de la historia y el único material del grupo sobre un escenario que se editó estando éste aún en activo.

Además, Presence tiene en mi cabeza una estructura muy bien definida, gracias a ser el disco más corto del grupo, junto a In Through The Out Door, en cuanto a número de canciones (siete cada uno) y también uno de los menos célebres (otro logro que comparte con su hermano menor). Así, y de manera totalmente simétrica, Presence dispone sus dos mejores canciones (y las más largas, dentro de un disco bastante largo si tenemos en cuenta el promedio de minutos por canción) enmarcando el disco, una en cada extremo. Justo en mitad del álbum, aparece la que yo creo que es la canción más conocida del mismo, y antes y después de ésta, encontramos dos canciones que yo considero bastante desconocidas para el gran público, dejando aparte a los fanáticos del grupo, por supuesto. No me gusta nada usar anglicismos si estos van a sustituir a palabras del idioma español que son perfectamente utilizables, pero a falta de un término mejor estos cuatro temas son verdaderos deep cuts dentro de la discografía del grupo, refiriéndome con esto a canciones muy alejadas de los éxitos o de las canciones más famosas de un artista. Y es que si bien en otros discos de LZ (mayormente en los seis primeros) el volumen de temas que son grandes éxitos del grupo, o inmensamente famosos, son mayoría en comparación con el resto (lo que serían esos temas escondidos), en los dos últimos discos de estudio del grupo pasa justo al revés.

La mastodóntica ACHILLES LAST STAND abre el disco de manera abrumadora y majestuosa, y si hay que empezar diciendo algo malo del álbum, por mínimo que sea, decir que después de esta canción ya todo es cuesta abajo en lo que a calidad musical se refiere. No quiero ser malinterpretado, ya que dicha afirmación ha de ir entre comillas, pues el disco me encanta y hay canciones más que dignas de hacer compañía a ésta y casi a la misma altura, pero es que Achilles Last Stand es una obra de arte y de hecho, me sería muy difícil sacarla de un hipotético top cinco de canciones de Led Zeppelin. Es además, con sus cerca de diez minutos y medio de duración, la segunda grabación en estudio más larga del grupo, sólo superada por IN MY TIME OF DYING (Physical Graffiti), que supera los once.

Es difícil analizar de manera detallada una canción como ésta, ya que la complejidad de la que acabo de hablar encuentra aquí su máxima expresión, algo que supone un nexo entre esta canción y gran parte de la discografía (sobre todo en su segunda mitad) del grupo. Otra característica típica de LZ que también podemos encontrar en este tema es que, a pesar de ser un grupo con un solo guitarrista, Page grababa en estudio varias guitarras (esto no es nada nuevo ni extraño, pero este señor lo llevaba a otros niveles), no sólo una rítmica y otra solista, creando unas cuantas capas que suponen una auténtica avalancha sónica al escuchar el tema (sobre todo con auriculares), con distintos riffs que entran y salen por cada altavoz. De hecho, por lo que leo por ahí, hasta se grabó más de un bajo en este tema. Después, todos ellos, y en especial Page, se las arreglaban para reproducir algo así en directo de la manera más fidedigna posible, teniendo en cuenta que, al fin y al cabo, eran un trío más la voz de Plant y en palabras del propio Page, en una canción como ésta podía haber perfectamente seis guitarras a la vez en según qué partes.

Todo empieza con una guitarra aislada, prácticamente limpia, que va aumentando de volumen hasta que antes de llegar a los veinte segundos empieza lo que es la parte más reconocible de la canción, que no es otra cosa que el galopante bajo de Jones (precursor de la inminente NWOBHM, o New Wave Of British Heavy Metal, y verdaderamente uno puede imaginarse a alguien como STEVE HARRIS, de IRON MAIDEN, ideando unas cuantas de sus inmortales creaciones con esta canción en mente), sobre el cual Page va tejiendo su telaraña (por lo visto influenciado por el tiempo que pasó con Plant en Marruecos, mientras el disco iba siendo ideado, y es que no hay que olvidar que el tema del exilio fiscal impedía a esta gente pasar mucho tiempo en Inglaterra; en cualquier caso, la influencia de Oriente Medio en la música del grupo no era a estas alturas ninguna novedad, pues la habían usado antes), junto al furioso golpeo de un Bonham que tendrá muchas oportunidades de demostrar en esta canción por qué es recordado como seguramente el mejor batería del género.

Antes del primer minuto Plant entra en escena para, poco a poco, desplegar con su grandiosa voz una larga letra que habla a partes iguales de la ya mencionada condición de exiliados fiscales de los miembros del grupo y de sus vivencias durante sus viajes en dicho exilio, con referencias a mitos como el del titán Atlas o Albión, siendo, curiosamente, la referencia del título al héroe griego Aquiles sólo una broma irónica relativa al accidente previo del cantante, en el que se lesionó seriamente el tobillo. Comparándose con Aquiles, que murió al alcanzarle una flecha en su tendón, Plant se refiere en dicho título y con ironía, a su año sin poder andar y al hecho de haber grabado el disco en una silla de ruedas. Para más señas, el título provisional de la canción, mientras ésta iba tomando forma, era The Wheelchair Song. Supongo que no hace falta traducir. Y para alguien que poco antes se había referido así mismo como un dios dorado (hay que decir que aquello no fue más que una broma) cualquier comparación parece escasa.

Alrededor del minuto cuatro llega un momento algo más relajado con el primer solo de Page, al que sigue una parte aún instrumental en la que se acaba el relax y dicha guitarra solista (y todas las que pueda haber por detrás) se pelea, por así decirlo, con el implacable ataque de Bonham, como si fuese un duelo guitarra-batería. Esto es algo que ya hicieron DEEP PURPLE algún año antes en su conocida y tremenda CHILD IN TIME (aunque no sé si esto es mera coincidencia) y que además me recuerda al final de la gloriosa interpretación que los también ingleses THUNDER (de quienes ya se ha hablado por aquí) hicieron en 1990 de su canción DON'T WAIT FOR ME en el festival de Donington de aquel año.

Pasado el quinto minuto la canción vuelve a sus derroteros habituales y Page va añadiendo nuevos dibujos al collage sónico (esté cantando Plant o no) en forma de más guitarras, y se suceden más de esos duelos anteriores junto a otras partes instrumentales y la voz de Plant, que al final tiende más a canturrear sólo sílabas, hasta que a falta de minuto y medio todo vuelve a la parte más habitual y conocida de la canción, antes de que ésta acabe muriendo (nuevamente en simetría), con la guitarra del principio, que se va apagando.

Achilles Last Stand es una de las dos únicas canciones del disco que el grupo tocaría en directo una vez que pudieron retomar su actividad en ese sentido. Por lo visto no estaban por la labor de ensayar material más asequible, con Page teniendo que idear la manera de tocar tantas guitarras con sólo una. Otro reto que esta banda no tuvo ningún problema en afrontar con éxito. Tanto que creo que esta canción apareció en todos y cada uno de los shows que el grupo dio antes de su disolución.

Entiendo que haya gente a la que esta canción le parezca excesiva, y en parte lo es, ya que sólo su duración la convierte en algo así, pero cuando se habla de exceso relacionándolo con repetición y aburrimiento ya no coincido. Insisto, difícilmente podría quedarse fuera de un top cinco de todas las canciones del grupo y algo así en este caso es decir mucho. Todo esto entra dentro de los gustos de cada uno, por supuesto, y desde luego no faltaron críticos que comentaron lo que acabo de decir, lo que quizás viene a resumir el conjunto del disco, como algo menos accesible que lo anterior, teniendo en cuenta que los seguidores del grupo estaban acostumbrados a más variedad y no sólo canciones como ésta. Pero vamos, que el recibimiento fue mayormente muy positivo e incluso se llegó a comentar que ésta fue la última pieza épica del grupo.

Inmortal.

It was an April morning when they told us we should go. And as I turned to you, you smiled at me. How could we say no?

Vamos con cosas menos complicadas con la enérgica FOR YOUR LIFE, cuyo riff principal (por lo visto Page usó aquí una Fender Stratocaster por primera vez, aunque tengo la duda sobre si pudo ser en la siguiente canción y no en ésta, o quizás en ambas; sea como fuere esto es algo muy raro en él, al ser básicamente un tipo unido casi siempre a una Gibson) parece contener algo de slide (otro anglicismo, pero de verdad que no sé si hay una palabra española para esto) y multitud de silencios. Plant domina el asunto haciendo buen uso de sus habituales canturreos en un tono mucho más desenfadado que el de la canción anterior, y a esas alturas de su carrera uno se imagina al cantante encarando una canción así sobre el escenario con tal confianza que podría hacerlo dormido y clavarlo.

A partir de poco después del segundo minuto la canción entra en territorio mayormente instrumental (aunque se cuelan algunas partes ya más breves de la letra y más excesos vocales de Plant), con distintos riffs que parecen ser variantes lógicas del principal y en general poco respiro, hasta el tardío solo de Page, que acaba pasado ya el minuto cinco. La canción vuelve al principio cerca del final y Page aprovecha para colocar el típico riff adicional que acompañe al principal (y que va por distinto altavoz) en la línea de Achilles.

For Your Life trata sobre las drogas, no sé si en relación con la adicción de un amigo de Plant, y aunque no la tocaron jamás en directo estando el grupo en activo, sí llegaron a tocarla por primera y única vez en el concierto que el grupo dio en el O2 de Londres en 2007 (diez de Diciembre), con motivo del homenaje a AHMET ERTEGÜN, cofundador y presidente de la discográfica británica ATLANTIC RECORDS. Dicho acontecimiento se convirtió en algo legendario y con una demanda brutal, al ser el único concierto completo que el grupo ha dado desde su disolución, y fue recogido en el disco en directo (más DVD) CELEBRATION DAY, editado en 2012. En dicho show el batería JASON BONHAM sustituyó a su padre por razones obvias y sí, de manera sorpresiva incluyó esta canción en el set list.

Wine and roses ain't quite over, fate deals a losing hand.

ROYAL ORLEANS es la canción más corta del disco y un tema muy movido e incluso bailable, con toques funk incluso, a partir de su segunda estrofa (aunque no hay un estribillo propiamente dicho). Tras repetirse el arranque guitarra-batería por segunda vez, Page añade en dicha estrofa unas guitarras muy funk, lo que da al tema ese aire festivo y bailongo. Hay un pequeño solo de Jimmy Page a partir de la mitad de la canción y lo demás es más de lo ya escuchado ya que tampoco hay para mucho más en una canción que no llega a los tres minutos, algo bastante extraño en este disco y en la carrera de LZ en general, bastante dados a componer temas mayormente largos o muy largos.

Ésta es la única canción del disco en la que todos los miembros del grupo comparten créditos y el título se refiere al hotel del mismo nombre que el grupo solía frecuentar al visitar Nueva Orleans. La letra, por su parte, parece contar una historia de un tío que se da cuenta de que la persona con la que ha pasado la noche, es otro hombre. Algo sobre drag queens, en relación con los bares de ambiente de la mencionada ciudad, que parecían ser del agrado del grupo por ser más divertidos y por evitar en ellos ser agobiados por multitudes en busca de autógrafos. Aquí mismo una historia acerca de la canción en relación con el bueno de Jones.

Hay que decir que LZ no contemplaban la edición de sus canciones como singles, algo más que habitual en la época, ya que veían sus discos como entes indivisibles que debían ser escuchados como tales, y en ese sentido el grupo y su afamado manager, PETER GRANT, fueron bastante explícitos al respecto, sobre todo en el Reino Unido. Pero aún así se editaron varios singles de sus canciones, sin su consentimiento y sobre todo en Estados Unidos. Royal Orleans fue la cara B de uno de ellos, el único que salió de este disco.

A man I know went down to Louisiana, had himself a bad, bad fight, and when the sun peeked through John Cameron with Suzanna, he kissed the whiskers left and right.

|

| John Paul Jones |

Colocada en mitad del disco (aunque abriendo su cara B en el vinilo) está la que antes he considerado como (seguramente) la canción más reconocida del disco, al menos en cuanto a fama popular, y que no es otra que NOBODY'S FAULT BUT MINE. Parte de esa fama viene por el hecho de ser esta canción uno de eso temas ajenos que el grupo adaptó (y en muchos casos hizo suyos) y que posteriormente han ido generando polémica por el tema de los créditos. Por eso no se sabe si este tema es una versión, una adaptación, un plagio o qué. Por comentar un poco sobre este tema (que en el caso de LZ ha sido bastante controvertido, aunque en algunos casos, y en mi humilde opinión, de manera ridícula), decir que esto no era algo nuevo ya en su día y de hecho es algo que un montón de artistas han hecho. No en vano, supongo que las raíces del blues y la música americana son muy lejanas y la autoría de muchas melodías simplemente no se conoce. Y versiones, por así decirlo, ha habido siempre. Sea como fuere, creo que es justo reconocer el crédito que tiene el autor si éste es conocido. Hasta aquí lo fácil, porque luego vienen las subjetividades y todo eso.

En el caso que nos ocupa, Wikipedia usa la palabra rendition, que podría traducirse como interpretación (aunque no sabría decir si hay alguna diferencia con lo que es una versión propiamente dicha). Supongo que versionar supone ser mayormente fiel al original, y en este caso lo que se hace es una interpretación personal de una canción que se llamaba IT'S NOBODY'S FAULT BUT MINE y que fue grabada por primera vez en 1927 por BLIND WILLIE JOHNSON, incluyendo además una letra distinta casi en su totalidad. Lo cierto es que escuchando la versión original no es tan fácil adivinar que se trata de la misma cosa (hay excesivas diferencias que no son sólo fruto del paso del tiempo), quitando la frase título, pero en los créditos aparecen Plant y Page como compositores y no sé si debería haber sido así. De hecho ellos mismos han reconocido querer grabar este tema, aunque con un arreglo distinto.

Sea cual sea la opinión de cada uno, y dejando de lado temas legales, la canción de LZ es un asunto completamente distinto. Una pieza de rock duro macarra y arrastrado que empieza con la guitarra aislada de Jimmy, con un sonido muy peculiar, como si pasada por algún efecto o filtro (de tecnicismos yo voy muy justo), a la que pronto le sigue Plant dando la réplica a la melodía con su voz, como si de una guitarra más se tratase. Pasado el primer minuto entra el resto del grupo, con Page usando otro riff, aunque repetirá unas cuantas veces la frase inicial e incluso toda esa primera parte, junto a la voz de Plant y la participación de Bonham. Es curioso, porque en esta canción se puede apreciar cómo éste último era capaz de hacer con un bombo lo que la mayoría de los baterías de la época seguramente no fuesen capaces de hacer con dos, tal es el sonido que consigue con su pie. Y luego está lo de su tremebunda y conocida pegada. Ninguna novedad. Cerca del minuto tres el asunto entra en ebullición con la parte instrumental liderada por la armónica de Plant, algo que se repetirá ya cerca del final con el solo de Page sustituyendo a dicha armónica. Al final encuentras con que los más de seis minutos que dura la canción se han hecho muy cortos.

La maestría de LZ con este tipo de material, digamos de aires improvisados, era legendaria, y al respecto de esta canción, el afamado productor RICK RUBIN (mencionado en la entrada sobre THE CULT) comentó que el grupo conseguía que algo que sonaba como una sesión improvisada tuviese una precisión digna de una coreografía.

Este tema es el otro de Presence que encontró su sitio en el repertorio en directo del grupo, en casi cada uno de sus conciertos posteriores, y además tuvo también su hueco en el show de 2007 que mencioné antes, en el que se comenta que Plant bromeó con la audiencia diciendo que la primera vez que habían escuchado esta canción había sido en una iglesia del Mississippi, en 1932. Si esto es así yo me lo he perdido, ya que en la versión en audio del concierto no lo escucho por ninguna parte, aunque es probable que la broma haya sido recortada. Tendré que echar un ojo al DVD.

En cuanto al contenido de la letra más diversidad de puntos de vista. Que si se mantiene el espíritu de la letra original, que habla de una lucha espiritual de la que se sale triunfante leyendo la Biblia, pero cambiando la religión por la heroína (la letra incluye la famosa frase monkey on my back, que se refiere a la adicción y al temido mono), que si Plant lamenta el supuesto pacto del grupo con el diablo (en relación con la canción HELLHOUND ON MY TRAIL, de ROBERT JOHNSON, que habría servido al grupo de inspiración), etc. Quién sabe. Y además, a quién le importa?

Trying to save my soul tonight, oh, it's nobody's fault but mine.

CANDY STORE ROCK es la primera de las dos canciones restantes que he colocado antes en la categoría de poco conocidas, por así decirlo, a pesar de ser una de las favoritas de Plant y haberse editado (sin mucho éxito) como single en Estados Unidos (exacto, su cara B fue Royal Orleans).

Se trata de una canción bastante escueta en cuanto a su duración y un homenaje al rock de un par de décadas antes. Por resumir, una canción con cierto aire de rock and roll, más que del rock duro habitual, pero interpretada por Led Zeppelin, lo que supone la omnipresente e incansable presencia de la batería de Bonham, que llena todo el tema, distanciándolo del sonido de la década en cuya música la canción supuestamente se inspira. Personalmente me gusta, pero está claro que no es una de las canciones por las que el grupo es recordado y venerado. Lo mejor es, en mi opinión, la misteriosa frase inicial de Page, a la que se acaba uniendo Bonham, y el breve y temprano solo del primero, que en su primera parte parece estar compuesto por acordes sueltos, por muy raro que algo así suene.

No fue interpretada en directo (repito, estando el grupo en activo, por lo que dejo de lado lo que pudiesen hacer Page y Plant años después) pero en Wikipedia se comenta que Page dejó caer un riff del tema en un concierto en Ohio en 1977.

He leído por ahí que la letra es una especie de collage formado por canciones de ELVIS PRESLEY ideado por Plant. No sé apenas nada sobre Elvis, así que ni idea tengo ni idea, pero lo cierto es que es la típica letra de deseo por una mujer, llena de metáforas (alguna bastante explícita) relativas a la tienda de chuches a la que se refiere el título.

Oh baby, baby, I like your honey and it sure likes me.

Sigue la también bastante festiva (a la par que desapercibida en la carrera del grupo) HOTS ON FOR NOWHERE, que hace una buena pareja con la canción previa (y con Royal Orleans, ya que estamos), dada la duración de ambas y el ya mencionado carácter desenfadado de ambas, aunque esto se reduce en este tema a la música, pues la letra muestra cierta amargura por parte de Plant, debida a la situación que atravesaba el cantante durante esta época. Por lo visto este tema se escribió en Malibú, pero por muy idílico que pudiese parecer el entorno hay que recordar que Plant estaba en silla de ruedas (the sun in my soul's sinking lower) y además alguna línea de la letra parece indicar cierta frustración con respecto a Page y Peter Grant, de quienes el cantante se quejaba por no mostrar empatía por su estado (I've got friends who will give me fuck all).

La canción, al igual que Royal Orleans (por ejemplo), arranca, para y vuelve a empezar, con Bonham en su abrumadora línea habitual, pero siendo Page quien se lleva las mejores menciones con su arsenal de trucos (el solo es buen ejemplo) y sus partes instrumentales con varias guitarras grabadas a la vez, que mejoran el resultado final. Me encanta el riff del guitarrista que llega cerca de cumplirse el cuarto minuto y que parece que va a ser el final de la canción, aunque ésta vuelve unos segundos más, sólo para que Page la termine volviendo a repetir dicho riff. Puede ser que en esta canción, Page volviese a usar la Stratocaster ya nombrada.

I don't ask that my field's full of clover, I don't moan at opportunity's door.

|

| Let the music be your master |

Uno tiene que coger aire a la hora de comentar la final TEA FOR ONE, y no solamente por la duración de la misma (unos nueve minutos y medio), sino también porque para el menda puede ser, junto a la genial THE ROVER (extraída de Physical Graffiti), la mejor canción del grupo después de descartar las diez o quince elecciones más obvias y famosas, a muchas de las cuales supera (también The Rover). Digamos que estos dos temas son, para mí, las dos mejores canciones menos conocidas del grupo. Como comenté antes, es, junto a Achilles Last Stand, lo mejor y lo más largo del disco, y de paso son estos dos los únicos temas del mismo sin un cierto aire alegre y vacilón.

Se trata de un mastodóntico y ultramelancólico (el título lo dice todo) blues que supuso un intento por parte del grupo de actualizar un poco lo que habían hecho en 1970 con SINCE I'VE BEEN LOVING YOU (una canción de su tercer disco, muchísimo más famosa pero en mi opinión bastante inferior a ésta, por mucho que esta opinión sea muy poco popular) y que habla de la añoranza por parte de Plant de su familia (por lo visto el cantante escribió la letra mientras estaba en un hotel neoyorquino tomando té él solo, y dicha familia es personificada en la canción por una mujer), ya que como ya se ha dicho antes, el grupo no sólo viajaba mucho debido a sus giras, sino que su condición de exiliados fiscales les obligaba a pasar mucho tiempo fuera de Inglaterra. Se comenta que Led Zeppelin eran partidarios de desechar material que hubiesen compuesto y que pudiese sonar demasiado similar a cosas que ya habían escrito en el pasado, pero hicieron una excepción en este caso, teniendo como referencia el aire y la estructura del ya mencionado blues anterior. Como apunte personal se me ocurre que este tema tiene bastantes similitudes con uno que el propio Page grabó años más tarde con DAVID COVERDALE para su proyecto COVERDALE - PAGE, que editó en 1993 un único disco de igual nombre. Dicho tema fue el genial (el disco entero lo es) DON'T LEAVE ME THIS WAY, pero no tengo ni idea de si hay alguna relación entra ambas canciones o simplemente es cosa mía. Este tema es más alegre que el de Led Zeppelin, en cualquier caso.

En cuanto a la música, el principio de la canción, sin embargo, no da la impresión de ser lo que finalmente va a ser, ya que durante los veinte primeros segundos nada indica la naturaleza tristona y arrastrada del tema. Esto cambia muy pronto y la canción se vuelve lenta, con Page haciendo de las suyas sobre el bajo de Jones y la lúgubre batería de Bonham, y así continúa el asunto cuando se une Plant, pasado el minuto y medio de canción. Me supera la frase del cantante en la que dice when a minute seems like a lifetime, oh baby when I feel this way, y que introduce lo que podría considerarse como una especie de estribillo, a pesar de no ser tal cosa, y en el que Page deja un poco de lado el blues para, por encima del mismo ritmo, dedicarse sólo a soltar una serie de acordes abiertos mucho más potentes y que hacen que pienses que la soledad de Plant puede tener remedio (alejando el tema del blues para alinearlo con el rock duro en cuya creación LZ fueron todo).

Pero no, porque los minutos vuelven a parecer vidas enteras y tras unas estridentes frases del guitarrista las aguas vuelven a su triste cauce. A partir de ahí se inicia una larga parte instrumental en la que parece repetirse toda la estructura previa, pero sin Plant, que vuelve cuando los acordes heavies regresan, habiendo pasado ya el sexto minuto. Todo esto, más las improvisaciones de Page, se repetirá hasta el final de este absoluto monumento musical con el que Presence termina.

How come twenty four hours, baby, sometimes seem to slip into days?

Como ya se ha dicho, en 2015 hubo reediciones bastante especiales de los discos de estudio del grupo, ya que en palabras de Page, todo lo relativo al trabajo de Led Zeppelin en estudio quedaba desempolvado, en forma de ediciones especiales con discos extra que incluían diferentes tomas de las canciones (que en algunos casos tenían incluso otros nombres) y en general material inédito de estudio.

Así, en el caso de Presence, el segundo disco de dichas ediciones especiales contenía cinco canciones, referidas como reference mixes of works in progress. Dichas canciones son TWO ONES ARE WON, que viene a ser una mezcla previa de Achilles Last Stand, For Your Life, 10 RIBS AND ALL / CARROT POD POD (POD), Royal Orleans y Hots On For Nowhere. Las tomas de las cuatro canciones que se incluyeron en el disco no difieren apenas de sus respectivas versiones definitivas, al menos musicalmente hablando, ya que si se nota algún cambio en la voz de Plant, sobre todo en Royal Orleans, que está cantada con una voz completamente distinta. En los comentarios de YouTube la gente fantasea con que sea Bonham quien canta, aunque no parece ser así.

Esto deja a 10 Ribs And All / Carrot Pod Pod (Pod) como lo más llamativo del segundo disco, siendo ésta una pieza instrumental mayormente guiada por el piano de Jones y que es todo lo contario al resto del disco y a la inmensa mayoría de las canciones del grupo. Es bonita como curiosidad, aunque me cuesta reconocer a Led Zeppelin aquí, sobre todo en su parte inicial sólo con piano. En cuanto al título y su significado, estoy tan perdido como es probable que el lector lo esté.

Y esto es todo. A Led Zeppelin le quedaban aún días de gloria en términos musicales, traducidos en más giras que hacer, récords de asistencia que reventar y discos que vender. Pero los días más amargos del grupo estaban a la vuelta de la esquina, primero con el fallecimiento de KARAC, el hijo de cinco años de Robert Plant a causa de un virus, a finales de Julio de 1977 (lo que ya trajo especulaciones acerca del futuro del grupo, como es lógico), y sobre todo con la también temprana muerte de John Bonham (un tipo absolutamente excesivo y por lo que he leído no muy aconsejable de tener cerca, a no ser que fueses parte de su círculo más íntimo) en Septiembre de 1980 y que, tras un par de meses de especulaciones, supuso que Led Zeppelin anunciaran su final definitivo en un comunicado emitido el cuatro de Diciembre de 1980 y firmado simplemente como Led Zeppelin. El grupo no podía existir sin uno de los cuatro miembros.

|

| Led Zeppelin en una foto promocional para sus dos shows en Knebworth, en Agosto de 1979. No habían vuelto a tocar desde la muerte de Karac, el hijo de Plant. El final estaba cerca |

Led Zeppelin dejarían el plano terrenal para entrar en la leyenda y después de aquello se suceden las carreras y proyectos, individuales o no, de los tres miembros restantes (siendo la de Plant la más prolífica) y los continuos rumores de reunión, que a pesar de no tener mayor fundamento duran ya más de cuarenta años. Ya di mi opinión sobre este tema en el apartado sobre Page de la entrada sobre los guitarristas, así que no hay nada más que decir.

Larga vida al dirigible y hasta otra!

ENGLISH

LED ZEPPELIN's (very likely to be the biggest band ever, at least for the one who signs this) exploits have been documented to the fullest, as well as their records have been examined, reviewed (in this case mostly for good, and overwhelmingly so) and slightly less than studied, borderlining on obsession (as usually happens with artists this big), and that's why there's no point in going back over the same thing, almost forty three years after their demise as a band, because everything has been said already.

So I won't be beating around the bush for very long, writing the customary introduction about the band, because, besides the futility of the whole thing, many things about the band were said on the guitar players entry, when I wrote about JIMMY PAGE. Those who might be interested can find the link to it here.

But despite all that, I'll venture to review one of their albums, going from one similarity between their career and BLACK SABBATH's during the seventies. Because both bands, besides musical bonds and their pivotal role in the creation and development of hard rock and heavy metal, their origin (all the musicians in both bands, barring Page and JOHN PAUL JONES hail from the Birmingham area), their shared friendship, the fame, the success and the debauchery, shared one curiosity in regard of their discography during that decade.

Sabbath's seventies run, with OZZY at the helm spans eight studio albums and, as I mentioned when I reviewed DIARY OF A MADMAN, the first six are very famous and succesful (I'll bring here, once again, the famed HENRY ROLLINS quote about only trusting yourself and the first six Sabbath albums) but the last two are surrounded by a mist of crisis and bad choices within the band, turning out to be two albums which not only are different, but also experimental and above all, failed.

In this regard, almost everyone with the minimum interest in the band, is familiar with BLACK SABBATH and PARANOID, both from 1970, MASTER OF REALITY (1971), VOL. 4 (1972), SABBATH BLOODY SABBATH (1973) and SABOTAGE (1975), and most of the songs on them need no introduction. But that does not apply to TECHNICAL ECSTASY (1976) ans NEVER SAY DIE! (1978), the weirdest, least succesful and least remarkable albums from that era of the band.

And the funny thing is that something similar happens to Led Zeppelin because, leaving aside the fact that both their first two albums were released in 1969, their seventies output is also comprised of another eight studio albums. And again, the first two from 1969 (LED ZEPPELIN I and LED ZEPPELIN II), are followed by LED ZEPPELIN III (1970), LED ZEPPELIN IV (1971), HOUSES OF THE HOLY (1973) and PHYSICAL GRAFFITI (1975), all of them very well-known, succesful and full of hits. And they also make six albums in total. But what about PRESENCE (1976) and IN THROUGH THE OUT DOOR (1979)?

Things change with them. Those records are neither as mentioned nor as succesful (keeping in mind is Led Zeppelin what we're talking about) as the other six. The latter, an experimental album really difficult to be pigeonholed which I don't quite get no matter how hard I try to listen to it thinking is not your average Zep music, matches to a great extent what I said about those two Sabbath albums (like them, it has some songs I really dig, three to be precise).

But Presence, the album I'm about to dig deep in, is a different matter and a very special album for several reasons. And besides, what's the point in going back to WHOLE LOTTA LOVE or KASHMIR for the umpteenth time? Many people, lots, have spoken and written about those songs and some other very famous ones by LZ much earlier than I have and much better too, no question. And also about Presence, of course, but I keep this ace up my sleeve about the charm which writing about LZ and a less expected album (with its very own doomed charm) of theirs entails. And, as far as I am concerned (this is where Presence distances itself from its follow-up and those two Sabbath albums), this one is a terrific album. I wouldn't lose my time talking around here about stuff I don't like, with all the many things I like and with all the time which I require to come up with a new idea and to put pen to paper with each entry. Moreover, I'll dare to make a really bold statement about Presence (not everyone's darling within the critic and the band's scholars, some of whom accused it, back in the day, of being rushed, uninspired, innecesary and even boring) because it is, together with LZ II and LZ IV, the band's best rounded-up album.

It only has seven tracks but man, this is going to be tough. Nothing seems to be simple or attainable with this band, not to mention the respect its name inspires to begin with.

In the mid-seventies Led Zeppelin were the biggest band in the world, dwarfing any other when it came to sales and shows attendance. Their tales about debauchery and excess (whether exaggerated or real) joined their musical status and there was no stopping the band (but is common knowlegde that the higher the ascent, the harder the fall). They had even created their own record label in 1974, SWAN SONG (named after a song which never made it onto Physical Graffiti and which ten years after would become MIDNIGHT MOONLIGHT, a song to be found on the album THE FIRM, by the short-lived band by the same name which Page formed with PAUL RODGERS in the eighties), whose logo (EVENING: FALL OF DAY, by WILLIAM RIMMER, 1869) with a winged human being is very well known and can be found in all kinds of LZ memorabilia. Said label published all Zep albums from that moment on and also some other artists, although it did not last long after the band's demise.

Presence came out on the thirty first of May, 1976, but it wasn't planned. LZ did not have in mind another studio album. They had been touring after the release of their previous album, Physical Graffiti (the first one to be issued by Swan Song, with a huge success on all fronts) in the beginning of 1975 and took some rest having in mind to go on with their touring activities later that year, but in August, ROBERT PLANT and his wife were involved in a serious car crash while vacationing in Rhodes. She almost died and Plant was injured to the point of having to be commited to a wheelchair, something which prevented him (and the band) from touring. Therefore, LZ saw themselves forced to change their schedule in the short and mid term.

All this led the singer, while his recovery (far from England, due to the band's status as tax exiles), to begin penning some lyrics, a work in progress joined by Page and which resulted in the idea of creating a new record (Presence, you guessed it). They began rehearsing in October, in Hollywood, when they were joined by Jones and JOHN BONHAM. This also meant that all the songs but one were written by the songwriting duo formed by singer and guitarrist, being the only one which wasn't a collective effort of the whole band.

Presence was produced by Page (who worked together with usual engineer KEITH HARWOOD) and was recorded at MUSICLAND studios, in Munich, in a very short time, because the ROLLING STONES had booked some studio time after them to record their BLACK AND BLUE album. Plant recorded his parts in his wheelchair, because of his injuries, and overall, what I read here and there about those rushed studio days is completely insane, mostly when it comes to Page (who, given the situation, took over the whole thing almost exclusively) and Harwood, for it is twenty hours-long work days what we are talking about.

It is said that, given the album was finished on the day prior to USA's Thanksgiving Day, Plant suggested it was called Thanksgiving, idea which was rejected favoring the definitive title, which referred to the aura or special presence which the members of the band felt when they worked together.

Concerning the cover, it is horrific. It was (and everything pertaining the design) another work by the artistic ensemble known as HIPGNOSIS (along with graphic designer GEORGE HARDIE), which prepared some pictures focused on a black central object called (in true original fashion) THE OBJECT, which aimed to picture the power of the band's presence, so powerful they did not need to be present (according to STORM THORGERSON, Hipgnosis' co-founder). The cover depicts one family sit at the table, surrounding said object, and in the background a marina with some sport boats can be seen. That marina had been artificially created on the occasion of one event in the mid seventies at London's EARL'S COURT ARENA, where LZ had produced 5 sold-out nights in a row at the beginning of 1975.

I have to admit that in 2015's reissue of the album, the front cover changes its colour and the black background and the rest of the variations make it much more appealling. As a curious factor, I have to note that the inner pictures were aimed to give the album the look of a NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC issue, and that the girl on the back cover was a certain SAMANTHA GATES, who had already appeared, along with her brother (STEFAN) on the famed and controversial cover for Houses Of The Holy, on which some naked children climbed Northern Ireland's GIANT'S CAUSEWAY.

And essentially there is not much else to say about the album before digging deep into its contents, besides saying that it was recorded by the very famous sole four members of the band (the moment one of them was missing, the band ceased to exist) and that, despite its success (it reached the top in USA and UK), it had mixed reviews and, as of today, it is the lowest selling LZ album.

Oh, I forgot! Very important curiosity about the album, because it's the only Zeppelin album on which no keyboards or additional instrumentation is played. Just guitar, bass and drums, plus harmonica on just one song and (I have to pay more attention for it's hard for me to notice it) some acoustic guitar on another, given the band focused more on hard rock and less on the relative diversity of previous records. On every Zep album, barring In Through The Out Door, there are monolithic hard rockers, together with some acoustic tunes, more experimental stuff and some nods to other styles, while Presence focused only on the first part, as if it was full of hard hitters such as ROCK AND ROLL, DAZED AND CONFUSED, THE OCEAN, CUSTARD PIE or OUT ON THE TILES, leaving aside stuff like GOING TO CALIFORNIA, on one hand, or IN THE LIGHT, on the other, while maintaining serious levels of complexity in some of the compositions. Let's not forget that Page is all over the album, something which makes perfect sense, given what it's been said about him and Plant beginning to work without the other two, during the time they spent together while the singer was recovering. Page took over the whole thing, not being Plant on top form, and it shows.

All this, together with the condition of the band during those times, meant that LZ were not able to tour presenting an album for the first time (Plant's injuries rendered the band unable to step onto a stage during the remainder of 1976) and the scarce presence of the album's songs in the band's live repertoire (some of them have been performed by Plant and Page during the post-Zeppelin years, being those the ones the band played back in the day or others, but I'll leave that aside), gives Presence a doomed flair, as I said. To top it all off, the album was somehow eclipsed by the premier, that same year, of the film THE SONG REMAINS THE SAME (which mostly showed the band playing New York's very own Madison Square Garden in 1973) and the release of its sonic counterpart, one of the most famous live albums ever and the band's sole stuff taped on stage to be released while Led Zeppelin were still active.

Presence has, in my thoughts, a very well defined structure, for being the shortest of their albums in terms of number of songs (tied with In Through The Out Door, with seven songs apiece) and one of their least famous (another achievement shared with its youngest brother) make it possible. Thus, in a symmetrical way, Presence is bookended by its two best songs (and the longest, within an album which is very long taking the average length of the songs into account). Just in the middle of the album, the song which I deem the most famous one can be found, and before and after this one there are two songs which are relatively unknown for the public at large (not counting the band's die-hards, of course). Some true deep cuts in their discography, and with that I mean songs which are not hits or among the most famous ones of an specific artist. Because LZ's previous studio albums were full of them, or almost, but the hits on the last two are in the minority if compared to the less known tunes.

The gigantic ACHILLES LAST STAND starts the album in an overwhelming and majestic manner and, if something bad needs to be said about the album, anything, maybe it is that after this song everything goes downhill when it comes to music greatness. I don't wish to be misunderstood, for this statement needs to go in quotation marks. I like this album very much and it has some songs more than worthy to go hand in hand with this one and almost on its same level, but the thing is that Achilles Last Stand is a masterpiece and, in fact, it would be really tough for me to leave it out of an hypothetical top five of LZ songs. It's also almost the longest studio recording of the band (clocking in at ten minutes and a half), only second to IN MY TIME OF DYING (Physical Graffiti), which lasts more than eleven.

It is tough to go into detail with a song like this, for the complexity I've just mentioned comes to the fore here, and in spades, and this fact links this song with most of the band's discography, mostly in its second half. Another usual LZ feature which can also be found here is that, despite being Page the sole guitar player in the band, he recorded several guitars at the same time in the studio (nothing out of the ordinary, but this person took it to another level), not only your average rhythm and lead guitars, creating layers of sound which mean an actual sonic avalanch when you get to listen to the song (mostly through a headset), with a huge array of riffs coming and going through the speakers. I read, in fact, that even more than one bass guitar was recorded for this song. Afterwards, while on stage, they managed to replicate something like that the most accurate way possible, considering that, after all, they were a threesome plus Plant's vocals and, in Page's own words, up until six guitars could be found on a song like this one, depending on the section.

It all begins with an isolated guitar, an almost clean one, which increases its volume before the most recognizable trait of the song arrives (by the twenty seconds mark), which is no other than Jones' galloping bass line (heralding the imminent NWOBHM, or New Wave Of British Heavy Metal, and one can truly envision someone like STEVE HARRIS, of IRON MAIDEN fame, coming up with the skeleton of some of their immortal classics with this song in mind), over which Page weaves his spiderweb (influenced by the time he spent with Plant in Morocco, while they were planning and composing the album, because let's not forget they had to spend most of their time abroad because of their tax exiles status; in any case, the Middle East influence was not new in LZ's music), together with Bonham's furious pounding, who will have many a chance throughout the song to show why he is remembered as probably the genre's best drummer.

Along comes Plant before the first minute to, little by little, roll out with his magnificent voice a story which tells both about their tax exile and everything they experienced while abroad because of said exile, referencing myths like Atlas the titan or Albion, and being, oddly enough, the title's nod to the famed greek hero, only an ironic joke related to the previous car crash in which Plant seriously injured his ankle. Comparing himself to Achilles, who died when hit by an arrow in his heel, Plant alludes ironically to his year without being capable to walk and to the fact that he recorded the album while confined to a wheelchair. Furthermore, the song's working title, was The Wheelchair Song. To someone who little before had referred to himself as a golden god (it needs to be said that was only a joke) any comparison looks meagre.

Around the four minute mark a more relaxed section arrives, featuring Page's first solo, followed by an instrumental part with no relax whatsoever and in which said lead guitar (and all that could be behind it) gets into a fight, so to speak, with Bonham's relentless attack, as if it was a guitar-drums kind of duel. This is something that had already been done before by DEEP PURPLE on his very famous and great CHILD IN TIME (don't know whether this is a coincidence or not) and which reminds me of the ending of the glorious live version that the also english THUNDER (about whom I have already talked about around here) did in 1990's Donington Park Festival of their own song DON'T WAIT FOR ME.

After five minutes the song goes back to business and Page adds new drawings to the overall sonic collage (being Plant singing or not) by way of more guitars, and more of those guitar-drums duels ensue, as more instrumental sections do, and Plant's voice becomes a humming. When there's only one minute and a half left the galloping bass comes back and the song eventually ends in symmetry with the beginning's clean guitar, which slowly fades away.

Achilles Last Stand is one of the only two songs on the album to be played live by the band when they were able to perform again. They just could not be content with playing easier stuff, so Page had to figure out how to play so many guitar parts with only one. Another challenge this band had no trouble overcoming, so much that I believe this song featured on every show the band played before its end.

It's understandable that this song might be deemed as excessive by many, because only its length makes it excessive no matter what, but when this excess relates to boredom or repetition I'm glad to disagree. And I insist, it's very difficult that this tune could be left out of a top five of the band's best songs, and in this specific case, this speaks volumes of Achilles Last Stand. This is all a matter of tastes, of course, and there was no shortage of people saying what I've just said, something which sums up the whole album somehow, as something less approachable than what they did before, taking into account that the fans were more used to more diversified stuff and not only to these kinds of songs. But the reception was overwhelmingly positive and it was also said that Achilles was the band's last true epic.

Immortal.

It was an April morning when they told us we should go. And as I turned to you, you smiled at me. How could we say no?

Let's go with less complicated stuff with the energetic FOR YOUR LIFE, whose main riff (apparently Page used a Fender Stratocaster for the first time here, although I'm not quite sure whether it was on this song or on the next one, or maybe on both; this is kind of weird for he was primarily known for being a guy always glued to a Gibson) seems to feature some slide guitar and plenty of silences. Plant dominates the whole thing putting his usual humming to very good use in a much happier mood than that of Achilles Last Stand, and at this point of his career one can perfectly picture the singer facing a song like this one on a stage so confidently that he could do it in his sleep and nail it.

Already in its third minute the song mostly works as a singer-less unit (although there are still some briefer segments of the lyrics and more vocal excesses courtesy of Plant), with different riffs which seem to be extensions of the main one, and little time to breath, until Page's late guitar solo, which ends well after the five minute mark. Back to square one when reaching the end and Page takes advantage to lay another additional riff which combines with the main one but through the opposite speaker, very much in the vein of Achilles.

For Your Life is about drugs, although I'm not sure whether this relates to some Plant's friend addiction or not, and was never played live while the band existed. But they did play it for the first and only time during the show they performed at London's O2 (December, the tenth), on the occasion of AHMET ERTEGÜN's tribute, who was both co-founder and chairman of the british label ATLANTIC RECORDS. Said show quickly became something legendary and heavily demanded, being the only entire concert Led Zeppelin have performed since they ceased to exist, and was taped and released as a live album plus DVD in 2012. Drummer JASON BONHAM replaced his dad for obvious reasons and yes, this song was given a chance on the set list.

Wine and roses ain't quite over, fate deals a losing hand.

ROYAL ORLEANS is the album's shortest piece and a very lively and even danceable tune, with some funk touches here and there, starting from the second verse (there is no proper refrain). After a second guitar-drums kickoff, Page lays those funk guitars in said verse and that adds to the merry flair of the whole thing. There's also a brief guitar solo in the second half and the rest is more of the same because there is not much room for more in a song which lasts less than three minutes, something unusual for this album and Led Zeppelin's career at large, being a band prone to write much longer and more complex songs.

Fun fact, this is the only song on the record on which all four members of the band share credit, and the song is named after a hotel they very often visited while in New Orleans. The lyrics tell a funny story about a man who realizes the person he has spent the night with is another man. Drag queens stuff, related to the gay bars in town they strangely were fond of because of being funnier and allowing them to go unnoticed, avoiding fans in search of signatures and so on. Right here a story concerning this song and poor Jonesy.

It needs to be said that LZ were against releasing their songs as singles, which was customary in those days, because they saw their records as entire entities which should be listened to as such, and in this sense, the band and their famed manager, PETER GRANT, were very explicit about it, mostly in the UK. But they could not help that some of their songs were released as singles, without their permission and mostly across the pond. Royal Orleans was a B side to one of them, the only one off this album.

A man I know went down to Louisiana, had himself a bad, bad fight, and when the sun peeked through John Cameron with Suzanna, he kissed the whiskers left and right.

Placed right in the middle of the album, and opening the vinyl's second side, is what I deemed before as the most famous song on the record, at least when it comes to popular consciousness, and which is no other than NOBODY'S FAULT BUT MINE. Part of the fame comes from being one of those songs LZ adapted (and made their own in many cases) and it resulted in subsequent controversy because of the credits and royalties. This is why one can't say whether this is a cover, plagiarism or what. Only for the sake of mentioning this issue a little in depth (which in LZ's case has become quite controversial and, in my humble opinion, quite foolish sometimes), let's say this wasn't new back in the day and tons of artists had done before. Not in vain, I guess blues and american music are deeply rooted in the past and the authorship of many tunes is simply unknown. And there have always been covers, so to speak. Be that as it may is only fair to acknowledge the credit of the author if they are known. So far, the easy part, because along come biases and all that.

Concerning this song, Wikipedia uses the word rendition, but I don't know if there's any difference with a proper cover. I guess that covering a song means being loyal to the original version, and in this case LZ do a very personal interpretation of a song called IT'S NOBODY'S FAULT BUT MINE, recorded for the first time in 1927, by BLIND WILLIE JOHNSON, with a text which is almost completely different. Truth is, listening to the original song is no easy task to notice it's the same thing (there are many differences which not only are the outcome of all the time passed by), leaving aside the title sentence, but Page and Plant are credited as songwriters and I don't think that is completely accurate. They, in fact, have admitted being willing to record the song but rearranging it.

Whichever anyone's opinion might be, and leaving legal issues aside, LZ's tune is a completely different affair. A vile and tacky hard rock number which begins with Page's isolated guitar, but with a very unusual sound, as if filtered through some kind of effect (I'm not big on technical concerns), soon followed by Plant, who replicates the guitar line as if his voice was another guitar itself. Once the first minute is gone the whole band jumps in, with Page leading with a different riff (even if he will replay the guitar intro and even the whole initial part), together with Plant's voice and Bonham's drums. Speak of the devil, you can notice how the guy was completely capable of playing with one bass drum what most of the drummers of his time were unlikely to play with two, such is the sound he gets with his foot. His well known and abusive pounding is also noticeable, no news here. Close to the third minute the song erupts with the instrumental section led by Plant's harmonica, which will be shown again closer to the end with Page's guitar solo replacing said harmonica. In the end, the six-plus minutes of the song's running time have flown as if they had been just two.

LZ's mastery of this kind of, let's say, unscripted stuff was legendary and, concerning this song, famed producer RICK RUBIN (mentioned on THE CULT's entry) said the band achieved that something which sounded as an improvised session had an accuracy worthy of a choreography.

This is the other Presence song to find a spot in the band's live repertoire, in almost every show after the release of the album, and it was also played in the 2007 show I mentioned before, during which Plant joked saying the first time they had listened to this song had been in a Mississippi's church, in 1932. If this joke was ever uttered by the singer I have missed it completely, for I cannot find it on the audio version of the show, although it could have been edited. I'll have to check the DVD.

Regarding the lyrics, more room for diverse points of view. It might keep the original text's spirit (a spiritual struggle you can overcome reading the Bible) but replacing religion by heroin (the lyrics mention the famous sentence monkey on my back, which refers to addiction and the dreaded withdrawal) or could it be that Plant regretted the alleged deal the band made with the devil (with reference to the song HELLHOUND ON MY TRAIL, by ROBERT JOHNSON, which could have inspired them). Who knows, and let's be honest, who cares?

Trying to save my soul tonight, oh, it's nobody's fault but mine.

CANDY STORE ROCK is the first of the two remaining songs which I have already tagged as deep cuts, so to speak, despite being one of Plant's favourites and being released as a (not very successful) single across the pond (correct, its B side was Royal Orleans).

It's a brief number, length-wise, and a tribute to the rock music of two decades prior. To cut a long story short, it is a song with a rock and roll vibe to it, more than the usual hard rock, but performed by Led Zeppelin, which means the tireless and almighty presence of Bonham's drumming, which fills the whole song, distancing it from the sound of the music the song is allegedly inspired by. I like it, even if it's not one of the songs this band is revered and remembered by. The best part is Page's mysterious intro, joined eventually by Bonham, and the former's short and early guitar solo, which seems to be comprised by open chords in its first part, as weirds as that sounds.

It was never performed live (again, while the band existed, so I'll leave aside what Page and Plant could have done after the band's demise) but Wikipedia says that Page played one of its riffs in a 1977 Ohio show.

I've read somewhere that the lyrics are some kind of collage of ELVIS PRESLEY's songs, devised by Plant. I hardly know anything about Elvis, so I could not say, but truth is, the song is about the desire for a woman, full of metaphors (some of them really explicit) related to the candy store the title is about.

Oh baby, baby, I like your honey and it sure likes me.

Follows the also lively (and almost unnoticed in the band's catalogue) HOTS ON FOR NOWHERE, which is a fitting companion piece to the previous tune (and to Royal Orleans, why not?), given their running time and the carefree nature of both of them, although this only applies to the music, for the text shows Plant's bitterness with reference to the times he was going through back them. Apparently, this song was written in Malibu, but as idyllic as the surrounding might look, it needs to be reminded that the singer was wheelchair-bound (the sun in my soul's sinking lower) and some lines may imply his frustration towards Page and Peter Grant, whom Plant had some complaints with for not showing enough empathy for his condition (I've got friends who will give me fuck all).

This song, as Royal Orleans (for instance) does, starts, stops and starts again, with Bonham in his usual thunderous line, but being Page who takes the prize with his endless bag of tricks (check the solo) and the instrumental sections featuring several guitars tracked at the same time, improving the final outcome. I love one of his riffs, very close to the four minute mark, which looks like the song's ending, although it comes bacl for a few seconds, only for Page to finish it with the same mentioned riff. He might have used the Stratocaster on this one as well.

I don't ask that my field's full of clover, I don't moan at opportunity's door.

And I simply have to catch my breath to talk about the closing track, TEA FOR ONE, not only because of its running time (nine minutes plus) but also because for yours truly it might be, together with the glorious THE ROVER (from Physical Graffiti), the band's best song once we have discarded the ten or fifteen most famous and obvious choices, which some of them it also overcomes (and so does The Rover too). Let's say these two songs are, in my opinion, Led Zeppelin's best deep cuts. As I said before, this is, together with Achilles Last Stand, the best and longest song on the album, and the only two songs without that lively flair to them.

It is a colossal and extremely melancholic (its name says it all) blues we are talking about, which meant an attempt of the band to update what they had done back in 1970 with SINCE I'VE BEEN LOVING YOU (a much more famous song from their third album, but way inferior to this, in my opinion, although I know it's an unpopular one) and which is about Plant's homesickness for his family (he wrote the text while staying in a New York hotel, drinking tea on his own, and his family is embodied by a woman in the song), because, as already mentioned, the band not only traveled a lot because of their touring, but there was also their condition as tax exiles, which meant spending too much time away from England. It is said that Led Zeppelin were prone to dismiss songs they had written if they sounded too similar to stuff they had already done in the past, but they made an exception with this one, using the mood and the structure of the aforementioned blues as the blueprint. As a personal afterthought it comes to mind that this song feels similar somehow to one that Page himself wrote some years after with DAVID COVERDALE during the COVERDALE - PAGE era, which saw them release their one and only namesake album in 1993. That song was the great (as pretty much the whole album is) DON'T LEAVE ME THIS WAY, but I don't know whether there is a connection between the two songs or I'm just daydreaming. This one is much more lighthearted than Zeppelin's though.

As for the music, the intro doesn't denote what the song is about to turn into, because during the first twenty seconds there is no clue of the crawling and sad nature of the song. It changes soon and the song gets slower, with Page doing his thing over Jones's bass guitar and Bonham's mournful drumming. And this is the way it goes on when Plant joing after the first and a half minute. The part when the singer says when a minute seems like a lifetime, oh baby when I feel this way, is simply devastating, and it introduces some kind of refrain in which Page forgets the blues for a while to unleash a string of powerful heavy metal open chords, over the usual tempo, which makes you think that Plant's loneliness might have a cure (distancing this song from the blues and bringing it closer to the hard rock music they were paramount in creating).

But to no avail, for minutes seem like entire lives again and after some screaming guitar lines the dust settles and sadness overflows once again. From that moment on a long instrumental section begins and it reproduces the previous structure without Plant, who comes back when the heavy chords do, after the sixth minute. It all goes on, together with Page's shenanigans, until the end of this musical monument which Presence ends with.

How come twenty four hours, baby, sometimes seem to slip into days?

As mentioned, in 2015 some special reissues of LZ's studio albums were released, because in Page's words, every bit of the band, studio-wise, had been dusted off and seen the light of day, with these special editions which had extra discs with alternative takes of some songs (some of them with different names) and, all in all, extra studio stuff.

With Presence, its second disc has five songs referred to as reference mixes of works in progress. Said songs are TWO ONES ARE WON, which is an early mix of Achilles Last Stand, For Your Life, 10 RIBS AND ALL / CARROT POD POD (POD), Royal Orleans and Hots On For Nowhere. The alternative takes don't differ too much from their final selves, at least when it comes to the music, for some changes in Plant's voice can be noticed, above all on Royal Orleans, sung with a completely different voice. On YouTube people fantasize with Bonham being the singer, although that does not seem to be the truth.

This leaves 10 Ribs And All / Carrot Pod Pod (Pod) as the most remarkable thing on the second disc, being this one an instrumental piece mostly led by Jones' piano and which is the opposite to the album itself and to the vast majority of the band's songs. It is beautiful, as a curiosity, even if is difficult to recognize LZ here, above all during the piano first part. As for its title, I'm as completely puzzled as the reader is very likely to be.

And this is all that there is. LZ still had many glory days ahead of them, music-wise, which translate into many touring to do, more groundbreaking attendance records to break and millions of albums to sell. But the band's most bitter days were also around the corner, first with the passing of Plant's five years old son, KARAC, due to a virus, by the end of July, 1977 (which already meant some speculating about the band's future, as it is understandable), and, above all, with Bonham's own untimely demise (a completely excessive person, and according to what I've read, someone not very advisable to be close to, unless you were really close to him) in September, 1980, which led to more serious speculations and, a couple of months after, to the band announcing that it ceased to exist, in a statement issued on the fourth of December and signed simply as Led Zeppelin. They could not go on without one of its four members.el hijo de cinco años de Robert Plant a causa de un virus, a finales de Julio de 1977 (lo que ya trajo especulaciones acerca del futuro del grupo, como es lógico), y sobre todo con la también temprana muerte de John Bonham (un tipo absolutamente excesivo y por lo que he leído no muy aconsejable de tener cerca, a no ser que fueses parte de su círculo más íntimo) en Septiembre de 1980 y que, tras un par de meses de especulaciones, supuso que Led Zeppelin anunciaran su final definitivo en un comunicado emitido el cuatro de Diciembre de 1980 y firmado simplemente como Led Zeppelin. El grupo no podía existir sin uno de los cuatro miembros.

Led Zeppelin would leave this mortal coil and began their journey through the mists of legend, and after that, solo careers (and also combined ones) of all the remaining members ensued (being Plant's the most prolific), as did the ongoing gossip about the band's reunion, which, despite being completely unfounded for the most part, go on for more than forty years already. I gave my opinion on the guitar players entry when I wrote about Page, so there's nothing else to say.

Long live Led Zeppelin and I'll see you soon!

Comentarios

Publicar un comentario

Comenta si te apetece, pero siempre con educación y respeto, por favor. Gracias!

Have your say if you want to, but be polite and respectful, please. Always. Thanks!